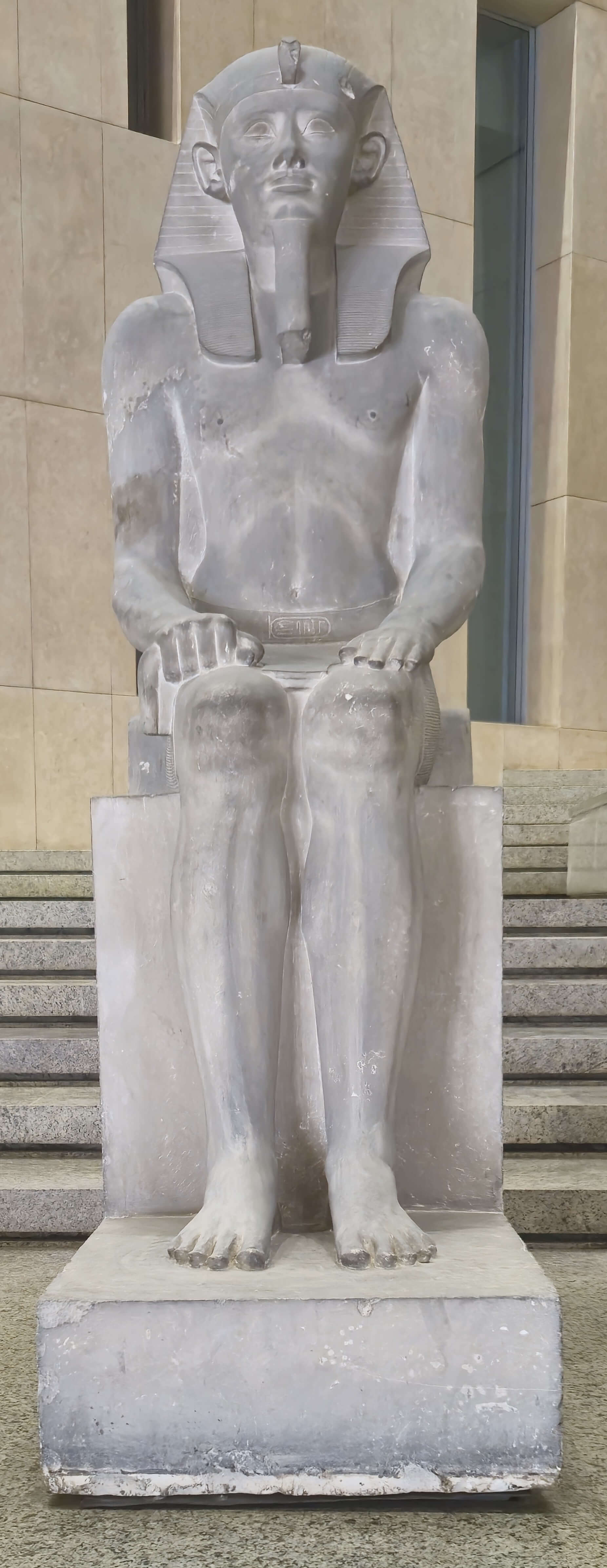

GEM 81974

King Senwosret I

Among the monumental legacies of Egypt’s Middle Kingdom, the reign of King Senwosret I (c. 1965–1911 BCE, 12th Dynasty) stands out as a time of political consolidation, artistic revival, and grand architectural ambition. This particular piece, carved from limestone and discovered at his pyramid complex in Lisht, is inscribed with the king’s royal cartouche and titles, including the epithet “the Good God” (netjer nefer), a designation emphasizing his divine nature and just rule.

What makes this statue particularly fascinating is the mention of two deities of the Nile—most likely Hapi of Upper and Lower Egypt—represented in inscriptions flanking the throne. In Egyptian tradition, the Nile was not merely a river but a living god who ensured fertility and abundance. The presence of these deities in the king’s statuary symbolizes Egypt’s prosperity and natural harmony under his leadership. Scenes of the Two Lands being united by the Nile gods appear frequently in Middle Kingdom art and emphasize the pharaoh’s role as the guarantor of cosmic balance (ma’at).

Senwosret I’s cartouche appears on multiple statues, stelae, and architectural elements from his reign. He ruled in co-regency w ... Узнайте больше с Премиум!

Разблокируйте полную историю этого артефактаПерейдите на Премиум, чтобы получить полный доступ к описанию, аудиогидам и эксклюзивному контенту для всех артефактов.Получите полный доступ к аудио и описанию главных экспонатов ГЕМ за 1.99$

Ищете другой артефакт?