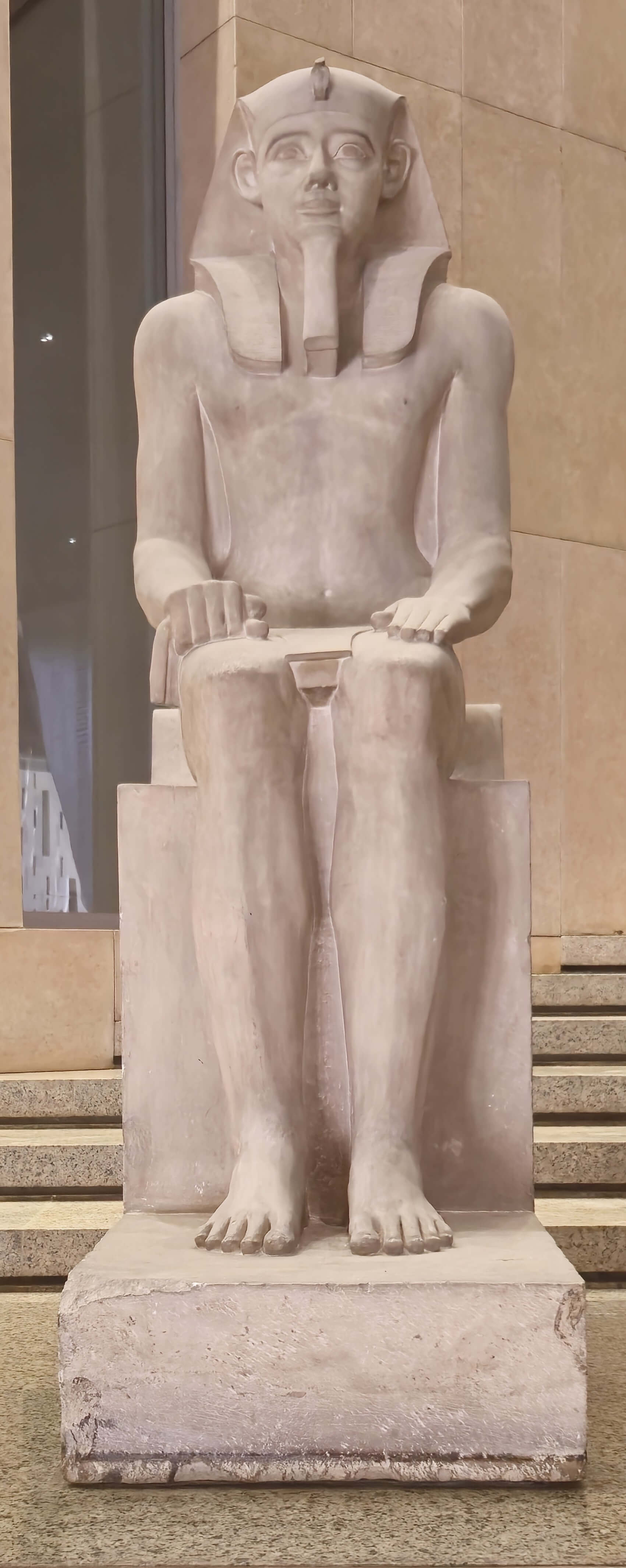

GEM 80524

King Senwosret I

In the heart of the Middle Kingdom, during Egypt’s 12th Dynasty, ruled one of its most capable and long-reigning monarchs—King Senwosret I, who ascended the throne around 1965 BCE and reigned for more than four decades. The artifact in question, part of his pyramid complex at Lisht, preserves traces of pigment on the face—hints of color once used to accentuate the eyes, eyebrows, lips, and possibly the royal beard and nemes headdress. This rare detail offers a glimpse into how vivid and lifelike these statues originally appeared, far from the monochrome stone surfaces we often associate with ancient sculpture today.

Senwosret I, also known by his throne name Kheper-ka-re, was the son of Amenemhat I, founder of the 12th Dynasty, and he co-ruled with his father for nearly a decade. His reign is considered one of the most stable and prosperous periods in Egyptian history. Under his leadership, Egypt expanded its influence into Nubia, secured trade routes, and strengthened administrative systems across the Nile Valley.

The king’s le ... Узнайте больше с Премиум!

Разблокируйте полную историю этого артефактаПерейдите на Премиум, чтобы получить полный доступ к описанию, аудиогидам и эксклюзивному контенту для всех артефактов.Получите полный доступ к аудио и описанию главных экспонатов ГЕМ за 1.99$

Ищете другой артефакт?