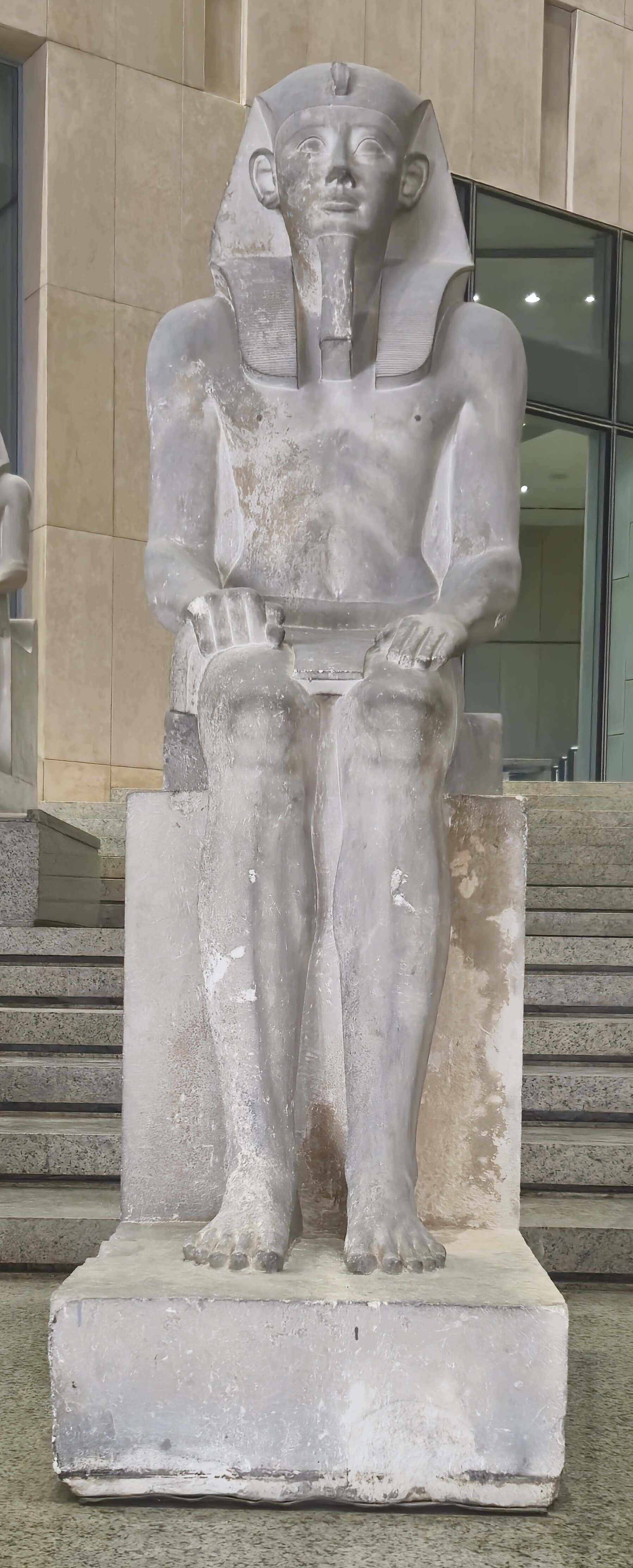

GEM 81971

King Senwosret I

In the golden age of Egypt’s Middle Kingdom, during the 12th Dynasty (c. 1965–1911 BCE), King Senwosret I reigned as a powerful and reformist pharaoh who left an enduring architectural and symbolic legacy. One of the most fascinating aspects of his statuary and throne imagery is the consistent use of unification motifs—powerful symbols expressing his sovereignty over both Upper and Lower Egypt.

The artifact in question, part of his pyramid complex at Lisht, shows the sides of a royal throne adorned with the “Sema-Tawy” symbol, which literally means “Union of the Two Lands.” This iconic emblem is made up of two entwined plants: the papyrus representing Lower Egypt (Delta region), and the lotus symbolizing Upper Egypt (the Nile Valley). These plants are often tied around a trachea and lungs, metaphorically uniting the breath and strength of the nation under one crown.

This symbol, repeated throughout royal iconography from the Old Kingdom onward, emphasized that the king was not simply a ruler of territory—but the divine personification of unity, stability, and cosmic order (Ma’at). On this throne, the unification is accompanied by hieroglyphic texts, likely prais ... Entdecken Sie mehr mit Premium!

Entsperren Sie die vollständige Geschichte dieses ArtefaktsWerden Sie Premium-Mitglied, um auf die vollständige Beschreibung, Audioguides und exklusive Inhalte aller Artefakte zuzugreifen.Erhalten Sie vollen Zugriff auf Audio und Beschreibung der wichtigsten Artefakte des GEM für nur 1,99 $

Suchen Sie ein weiteres Artefakt?