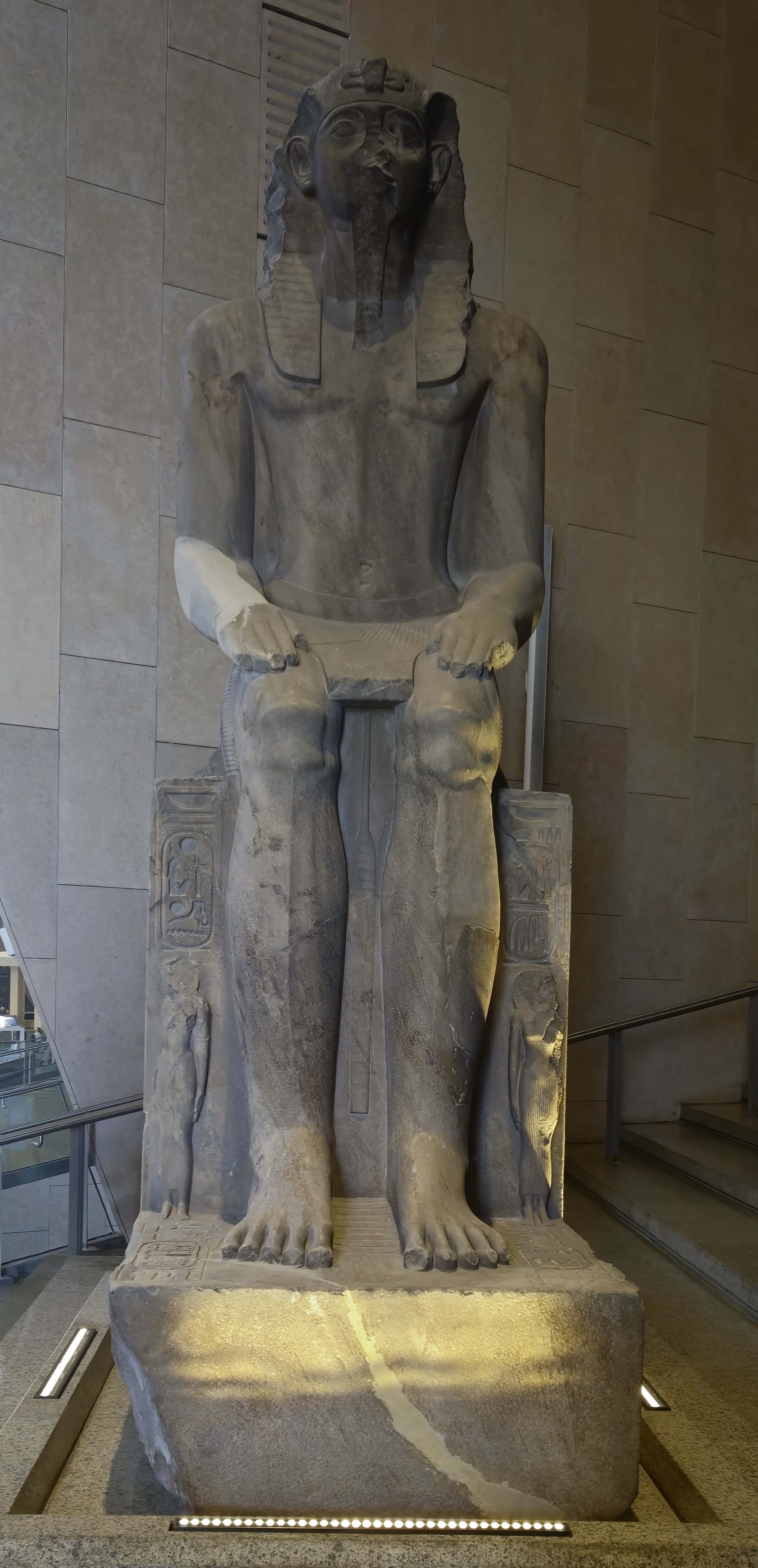

GEM 45808

Colossal Statue of a Middle Kingdom King

In the shadows of a small temple near modern-day Fayum, archaeologists unearthed a massive and intriguing statue from Middle Kingdom Egypt, likely depicting Senwosret III or perhaps his son Amenemhat IV. Standing tall in regal authority, the statue is accompanied by two smaller figures—thought to be princesses—positioned beside the king’s legs. These figures reflect the common practice in Egyptian royal statuary of portraying daughters or queens in supportive, symbolic roles to emphasize dynastic continuity and divine family order.

While the exact identity of the pharaoh remains uncertain, scholars lean toward Senwosret III, one of the most powerful and reformist rulers of the 12th Dynasty (c. 1870–1831 BCE). Known for his military campaigns into Nubia and his centralization of administrative power, Senwosret III worked to unify Egypt internally while expanding it beyond its borders. His reign marked a peak in Middle Kingdom strength, bureaucracy, and monumental art.

The statue is particularly significant because it was later reinscribed during the Ramesside Period, possibly during the reign of Ramses II, a full 600 years later. Such re-inscription was a comm ... Entdecken Sie mehr mit Premium!

Entsperren Sie die vollständige Geschichte dieses ArtefaktsWerden Sie Premium-Mitglied, um auf die vollständige Beschreibung, Audioguides und exklusive Inhalte aller Artefakte zuzugreifen.Erhalten Sie vollen Zugriff auf Audio und Beschreibung der wichtigsten Artefakte des GEM für nur 1,99 $

Suchen Sie ein weiteres Artefakt?