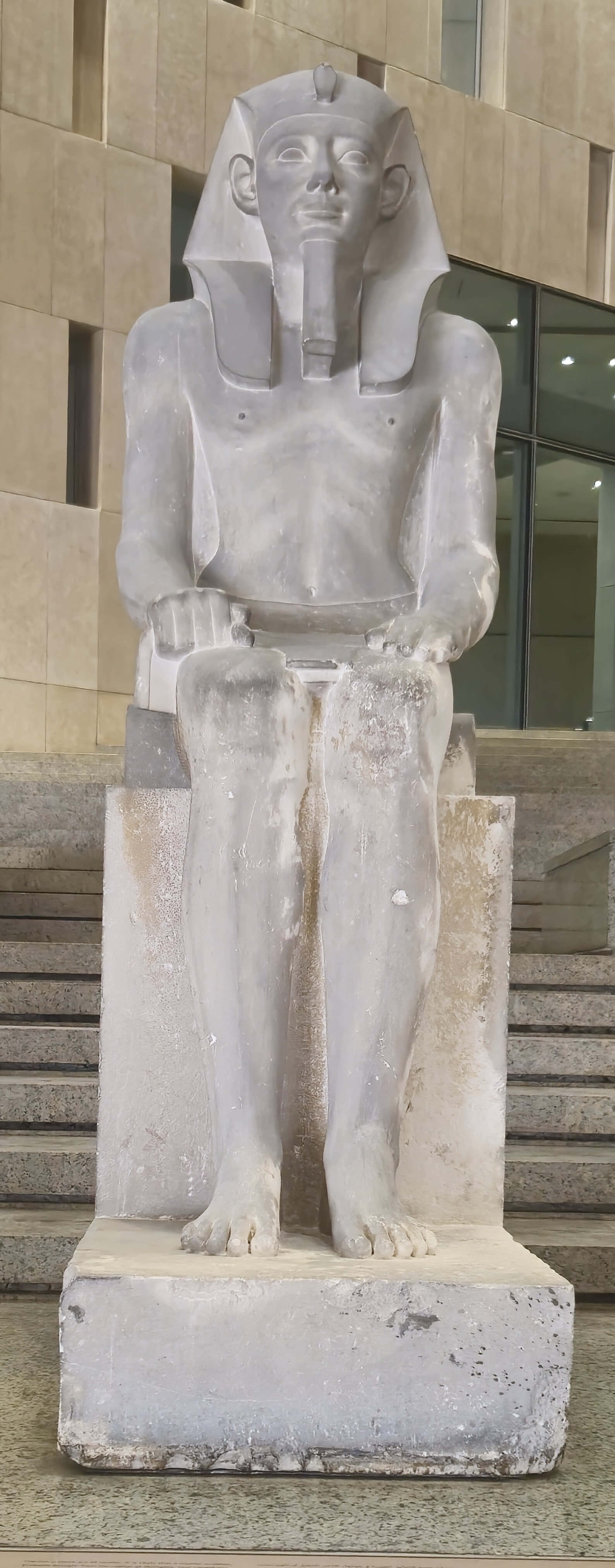

GEM 81973

King Senwosret I

During the reign of King Senwosret I (c. 1965–1911 BCE) of Egypt’s 12th Dynasty, the royal workshops achieved a remarkable level of standardization in statuary production—particularly for images of the pharaoh. This specific piece, from his pyramid complex at Lisht, is one of ten nearly identical statues, all portraying the king with a consistent style, posture, and regalia.

According to scholars and the inscription provided, it is likely that a master sculptor—perhaps working in Memphis, Egypt’s administrative center—crafted a prototypical model, or “master image,” of the king. This initial statue likely embodied all the stylistic ideals of Senwosret I’s reign: a calm, symmetrical face; royal regalia including the nemes or khat headdress; and a compact, upright body posture representing stability and divine authority.

Once this original was approved, it served as a template. Other craftsmen in the royal workshops, possibly apprentices or regional artisans, were then tasked with replicating the image. These replicas would be distributed throughout temples, mortuary complexes, and regional administrative centers. Despite their overall uniformity, close insp ... Discover more with Premium!

Unlock the Full Story of This ArtifactUpgrade to premium to access the complete description, audio guides, and exclusive content for all artifacts.Access the full audio and description for the GEM's main artifacts for only $1.99

Looking For Another Artifact ?